Physicians' knowledge, attitude and practices towards autopsy in a Nigerian tertiary hospital

SA Olowookere1, AO Komolafe2, AA Abiodun3, JG Omole4, A Babalola1, O Sanni1, J Ajala1, E Akande1 and T Ifogah1

1 Department of Community Health, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

2 Department of Morbid Anatomy, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

3 Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

4 Department of Physiological Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to:

Dr SA Olowookere,

Department of Community Health, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Email: sanuolowookere@yahoo.com

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Abstract

The post-mortem examination is a hospital service necessary to diagnose the cause and circumstances surrounding patients' death. This study assessed the knowledge, attitude and practices of physicians towards autopsy. Descriptive cross-sectional study of physicians that completed a semi-structured questionnaire assessing their knowledge, attitude and practices towards autopsy. Data collected were analysed. A total of 206 physicians participated. Most were young (69.4%), resident doctors (81.6%), in surgical specialties (52.9%) and Christians (72.8%). Majority had good knowledge (91.7%), positive attitude (81.1%) and positive practices (81.6%) of autopsy. Significant variables associated with good autopsy practices include age 35 years and above (OR = 3.23, 95% CI = 1.56-6.67, p = 0.002), Christianity (OR = 4.69, 95% CI = 2.24 – 9.84, p < 0.001) and positive attitude (OR = 21.15, 95% CI = 8.91 – 50.25, p < 0.001). Some physicians had poor knowledge, negative attitude and poor practices to autopsy. These physicians should be targeted in trainings on autopsy practices.

Keywords: attitude; autopsy services; knowledge; physicians; practices

Introduction

The autopsy or post-mortem examination is the gold standard of unravelling the mysteries about patients' health when fatalities occur(1-3). It involves the systemic dissection of the patient's corpse after death exclusively for medical and medico-legal reasons(4,5). The autopsy is done to establish the cause of death, detecting lesions that were not obvious on clinical examination and investigations, ascertaining the exact progression of the disease, proper staging of diseases such as malignancies, clarifying diagnostic controversies especially when reports of investigations vary and seem to contradict one another and confuse or confound the managing team(6,7). Autopsies also help to resolve relatives' doubts about the management of their deceased loved ones(8,9). Though the benefits of the autopsy seem interminable, there has been reduction in the rates of autopsy request by clinicians worldwide in the last three decade particularly(9-11). Reasons adduced for the decline include the over-reliance of clinicians on the over-hyped versatility of the investigative capacity of the modern sophisticated medical equipment such as computerised axial tomography scanning and medical resonance imaging equipment, the certainty of diagnoses by medical experts, non-assent by relations, religious prejudices and poor communication between the clinicians and the pathologist(12-14). There is also the subtle fear of medical litigations arising from autopsy revelations of misdiagnoses, missed diagnoses, clinical negligence and medical malpractice(15,16). The assumed judicial role by the self-righteous pathologist with inflamed academic pride to criticise and condemn the clinicians has also caused irritable withdrawal by clinicians demonstrated by failure to request for post-mortem examinations even in coroner's cases(16,17). The poor attitude of some pathologists to conduct autopsies with due diligence and generate a post-mortem correspondence to address the reservations of the clinicians has also led to the lack of interest in the autopsy by the clinicians(17,18). The failure of clinicians to request for clinical autopsies has resulted in sharp reductions in the conduct of autopsies by pathologists in many jurisdictions with resultant poor knowledge of the role of post-mortem examination in the care of patients among healthcare providers, undergraduates, physicians in training, postgraduate students of the health professions, young medical specialists and of course has emboldened the ignorance of the lay public(18,19). The result of the reduction in refusing to request, assessing and conducting post-mortem examination is an evidence of the failure of clinical systems pathology(19). Clinical systems pathology enables the rational design and testing of effective personalised predictive medical intervention and preventive measures for optimum patient centered care(20).

This study assessed the knowledge, attitude and practices of physicians working at the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria to autopsy.

Materials and Methods

Study location:

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study of physicians working at the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. The hospital has several medical, surgical, laboratory departments including the Department of Morbid Anatomy and Forensic Medicine with full complements for histopathology, toxicology and forensic autopsy including embalmment services. The hospital serves as a referral centre for Osun State and other States in the South western part of Nigeria and beyond.

Study design:

The study population include physicians working at the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Inclusion criteria:

Inclusion criteria were all physicians working at the various clinical departments including the emergency, clinics and wards.

Exclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria were physicians who did not consent to participate or who were not on duty during the study period.

Sample size calculation:

The sample size of 100 was calculated using an appropriate statistical formula for descriptive health studies [n=Z2pq/d2] with 12.5% physicians previously consented to autopsy and non-responders were taken into consideration(7,21).

Ethical considerations:

Eligible physicians after an informed consent completed a self-administered pretested semi-structured questionnaire that assessed autopsy knowledge, attitude and practices. The physicians were allowed to complete the questionnaire in their spare time at their convenience. Questionnaire information were anonymised.

The ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Statistical analysis:

Data obtained were analysed using SPSS version 16. Simple descriptive and inferential statistics were done. Test of significance was conducted using appropriate statistical methods. Bivariate regression analysis was performed to evaluate socio-demographic variables and other variables that are independently associated with good autopsy practices. Odd ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were presented and used as measures of the strength of association. Significant level was put at p < 0.05.

Results

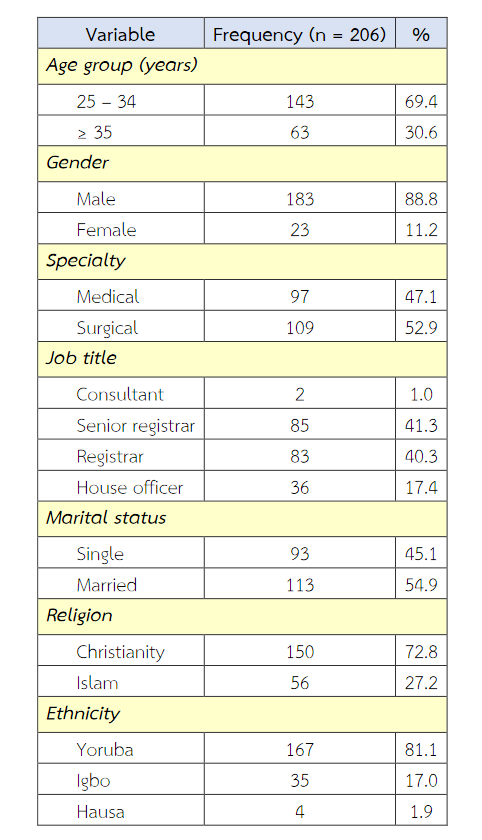

Out of 300 physicians approached to participate in the study, 16 declined, 37 did not return their questionnaire while 41 questionnaires were not included in analysis because of non-completeness. A total of 206 questionnaires with completed data were analysed (response rate 68.7%). The mean age of the study participants was 31.8 years, range 25 – 49 years. Most were young (69.4%), resident doctors (81.6%), in surgical (52.9%) and medical (47.1%) specialties. Most (54.9%) were married and Yoruba (81.1%). There were 150 (72.8%) Christians and 56 (27.2%) Muslims (Table 1).

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of physicians.

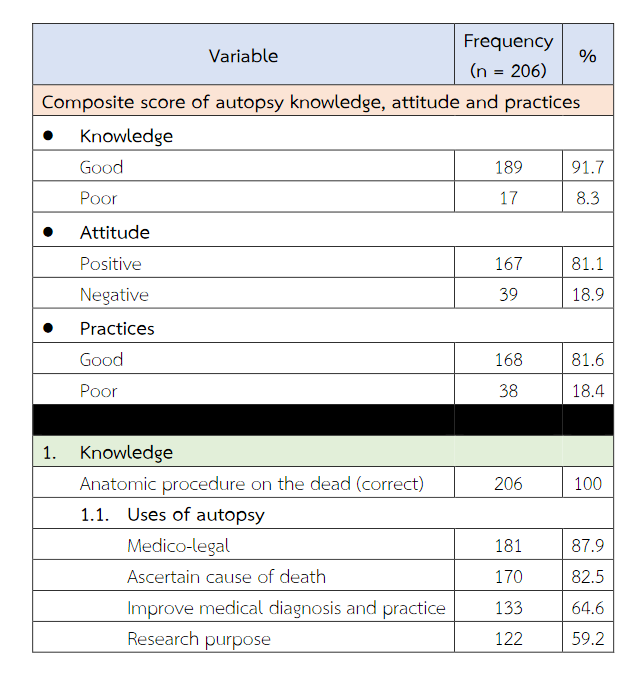

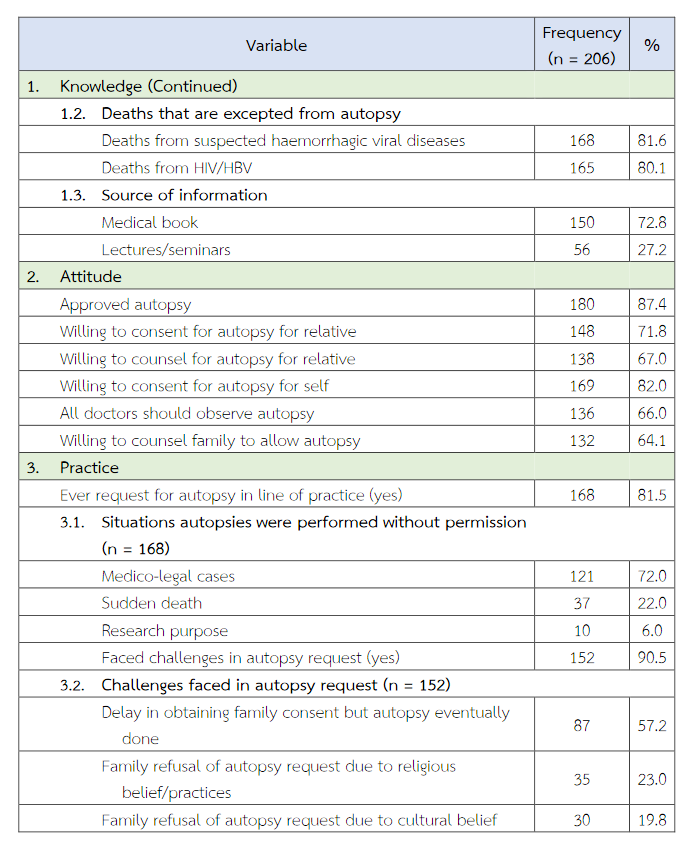

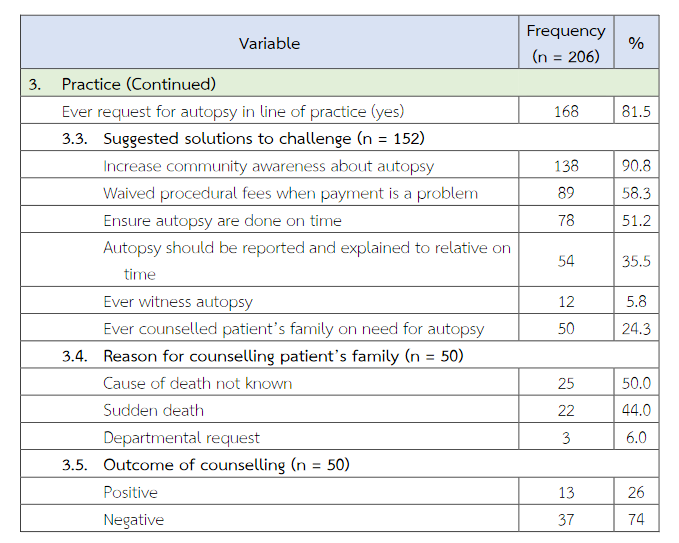

Table 2 reported the knowledge, attitude and practices towards autopsy. Majority had good knowledge (91.7%), positive attitude (81.1%) and good practices (81.6%). All the participants correctly defined autopsy with specific uses identified as medicolegal (87.9%), cause of death (82.5%) and deaths excepted from autopsy including those occurring in suspected haemorrhagic viral diseases (81.6%) and HIV/HBV (80.1%). Majority were willing to consent for autopsy for self (82.0%) and relative (71.8%). Also, majority believed that doctors should observe autopsy (66.0%) and were willing to counsel family to allow autopsy (64.1%). Majority have ever requested for autopsy in line of practice (81.5%), with challenges faced in autopsy request including delay in obtaining family consent (57.2%), or refusal of family in allowing autopsy due to religious practices (23.0%) and cultural belief (19.8%). Suggested solutions to these challenges include Increasing community awareness about autopsy (90.8%) and waived procedural fees when payment is a problem (58.3%).

Table 2 Autopsy knowledge, attitude and practices.

Table 2 (Continued) Autopsy knowledge, attitude and practices.

Table 2 (Continued) Autopsy knowledge, attitude and practices.

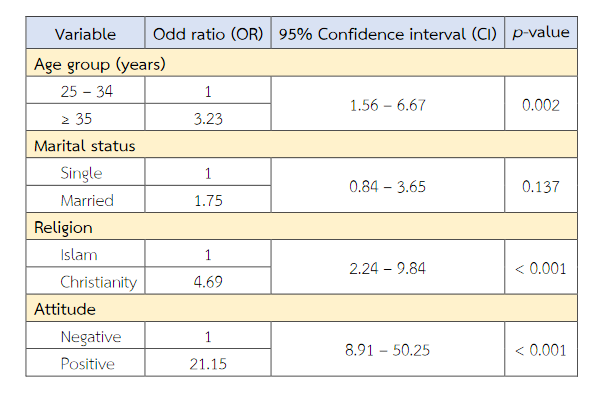

Table 3 reported the bivariate analysis of selected variables and autopsy practices among physicians. Significant variables associated with good autopsy practices include age 35 years and above (OR = 3.23, 95% CI = 1.56 – 6.67, p = 0.002), Christianity (OR = 4.69, 95% CI = 2.24 – 9.84, p < 0.001) and positive attitude (OR = 21.15, 95% CI = 8.91 – 50.25, p < 0.001).

Discussions

This study assessed the autopsy knowledge, attitude and practices of physicians working in a teaching hospital. This study finding reported that physicians have good knowledge, positive attitude and good practices towards autopsy. This finding differs from recent studies that reported that autopsy is no longer routinely requested by physicians for several reasons which included fears of litigations from family and other aggrieved parties(7-11). However, this study found that autopsy is rather requested for to avoid litigations, ascertain the definitive cause of death and improve medical diagnosis and practice.

Table 3 Bivariate analysis of selected variables and autopsy practices among the study population.

This study reported that deaths from suspected epidemic prone diseases such as haemorrhagic viral diseases are exempted from autopsy follow international practice to reduce the spread of such diseases to these healthcare workers and their close contacts including other patients and family members(22-24).

Also, the study reported that physicians were willing to consent to autopsy for self and relatives. They counsel relatives of dead patients to consent to autopsy so as to improve medical practice. This finding is in contrast with some studies that reported that health workers were averse to autopsy due to litigation fears(23-28). This could be because most deaths in some environment are usually taken to be either Gods wish which cannot be changed or has a diabolical cause or due to the witches and wizards hence the risk of litigation is very low(25-27). However, this spiritual believes and practices of burying the dead immediately by the Islamic faith could be responsible for some physician using religious believe as the basis for not requesting for autopsy or the relatives refusing autopsy(7,13,25).

Also, majority of the physicians believed that doctors should observe autopsy and were willing to counsel family to allow autopsy. A previous study among physicians in Ibadan reported that only 12.5% were willing to observe autopsy which is quite low when compared to our study finding(7). This suggests remarkable positive attitude to autopsy improve with provision of more awareness creation activity.

The suggested solutions to challenges face in allowing autopsy include waived procedural fees when payment is a problem. This is related to high poverty level in the study area where majority earned below the poverty level. Increasing awareness with partial or total reduction in procedural fees could increase acceptance of autopsy by the family members. Also, prompt reporting and giving feedback to family members could increase autopsy uptake by family members.

The factors associated with good autopsy practices include older age, religious belief and having positive attitude to autopsy. The older physicians were more experienced hence were more likely to request and encourage autopsy than younger doctors. Also, the doctors with the Islamic faith when compared to those with Christianity faith tend to resist autopsy because of their religious believes. Previous studies have reported religious objection to be a major hindrance to autopsy (7-9,13).

This study being questionnaire based cross-sectional obtain information whose content may differ from actual behaviour of our respondents. It will be difficult to generalise the study findings as the study was conducted in a site in southwest Nigeria.

Conclusions

Generally, physicians demonstrate good knowledge, positive attitude and good practices towards autopsy. However, some physicians had poor knowledge, negative attitude and poor practices to autopsy. These physicians should be targeted in trainings on autopsy practices. Hospital should have postmortem management committees to train young physicians on counselling skills and counsel relatives of dead patients. Refresher courses on autopsy targeting the consultants will improve training of residents on counselling for the postmortem. The government should also put policies in place that enforces the postmortem examinations especially when the cause of death is unknown especially for coroners' autopsies. Government may also give waivers or subsidise autopsy fess in order to make more people to consent to the procedure.

References

- Nakhleh RE, Baker RB, Zarbo RJ. Autopsy result utilization. A College of American Pathologist q-probe study 256 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999; 123: 290-295.

- Komolafe AO, Titiloye NA. Essentials of Autopsy Pathology. Niger J Fam Pract. 2016;7(1):7–14.

- Turnbull A, Osborn M, Nicholas N. Hospital autopsy: Endangered or extinct? J Clin Pathol. 2015; 68(8): 601–4.

- Van den Tweel JG, Wittekind C. The medical autopsy as quality assurance tool in clinical medicine: dreams and realities. Virchows Arch. 2016; 468(1): 75–81.

- Burton JL, Underwood J. Clinical, educational and epidemiological value of autopsy. Lancet. 2007; 369(9571): 1471–80.

- Talmon G. The use of autopsy in preclinical medical education. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010; 134: 1047–53.

- Oluwasola OA, Fawole OI, Otegbayo AJ, Ogun GO, Adebamowo CA, Bamigboye AE. The autopsy knowledge, attitude, and perceptions of doctors and relatives of the deceased. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009; 133(1): 78–82.

- Mjörnheim B, Rosendahl A, Eriksson LC, Takman C. Attitudes of nurses and physicians about clinical autopsy in neonatal and adult hospital care: A survey in Sweden. Nurs Res. 2015; 64(4): 264–71.

- Agboola AOJ, Izegbu MC, Oyebadejo TY. Necropsy request behaviour of clinicians: A study from a University Teaching Hospital in Nigeria. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2009; 25(4): 650–5.

- Geller SA. Who will do my autopsy? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015; 139: 578-580.

- Hebert TM, Maleki S, Vasovic LV, Arnold JL, Steinberg JJ, Prystowsky MB. A team-based approach to autopsy education. Integrating anatomic and clinical pathology at the rotation level. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014; 138: 322-327.

- Keys E, Brownlee C, Ruff M, Baxter C, Steele L, Green FHY. How well do we communicate autopsy findings to next of kin? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008; 132: 66-71.

- Atanda A, Umar A, Yusuf I, Imam M, Sule A. Autopsy and religion: A review of the literature. Sahel Med J. 2016; 19(3): 119.

- Lanjewar DN, Sheth NS, Lanjewar SD, Wagholikar UL. Analysis of causes of death as determined at autopsy in a single institute, the Grant Medical College and Sir J.J. Hospital, Mumbai, India, between 1884 and 1966 a retrospective analysis of 13024 autopsies in adults. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019: 1-6.

- Siebert JR. Increasing the efficiency of autopsy reporting. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009; 133: 1932-1937.

- Marshall HS, Milikowski C. Comparison of clinical diagnosis and autopsy findings six year retrospective study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017; 141: 1262-1266.

- Lorpocaro CG, Tester DJ, Maleszewski JJ, Kruisselbrink T, Ackerman MJ. Confirmation of cause and manner of death via a comprehensive cardiac autopsy including whole exome next-generation sequencing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014; 138: 1083-1089.

- Krywanczyk A, Mount S. In defence of academic autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018; 142: 157-158.

- Laposata M. A new kind of autopsy for the 21st century medicine. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017; 141(7): 887-888.

- Pacheco MC, Reed RC. Pathologist effort in the performance of fetal, perinatal and pediatric autopsies a survey of practice. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017; 141: 209-214.

- Kish L. Survey sampling. John Wiley and Sons, N.Y. 1965.

- Rim KT, Lim CH. Biologically hazardous agents at work and efforts to protect workers' health: A review of recent reports. Saf Health Work. 2014;5(2):43–52.

- Goldman BI, Reviving the hospital autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016; 140: 503-504.

- Kaschula ROC. The pediatric autopsy in Africa. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013; 137: 756-766.

- Malami SA, Mohammed A. Autopsy practice in northern Nigeria. The Nigerian Journal of Surgical Research. 2002; 4(3): 119-121.

- Ekanem VJ, Akhigbe KO. Attitude of Nigerian medical students towards autopsy. Turk J Med Sci.2006; 36: 51-56.

- Pelemo OE, Sabageh D, Komolafe AO, Sabageh AO, Odesanmi WO. An autopsy review of sudden unexpected natural deaths in a suburban Nigerian population. Population Health Metrics. 2014; 12(26): 1-6.

- Chattopadhyay S, Shee B, Sukul B. Unindentified bodies in autopsy-a disaster in disguise. Egyptian Journal of Forensic Science. 2013; 3: 112-115.